Get ready for the grand finale! Our historical introduction to Spartacus: Rome Under Threat concludes with a dramatic showdown that will leave you on the edge of your seat.

Don’t miss out on this thrilling conclusion! Read the previous chapters here and prepare to be captivated by the story of Spartacus.

– Part 1

– Part 2

– Part 3

After suppressing Quintus Sertorius’s rebellion in Hispania, Pompey’s legions were returning to Italy. While sources differ on whether Crassus had specifically requested reinforcements, the Senate seized the opportunity of Pompey’s return to Italy and ordered him to bypass Rome and head south to assist Crassus in suppressing the slave revolt. To further bolster Crassus’s forces, the Senate also dispatched reinforcements under the command of Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus, the proconsul of Macedonia.

Apprehended by the prospect of losing credit for the war to the arriving reinforcements, Crassus intensified his efforts to swiftly quell the slave revolt. Spartacus, anticipating Pompey’s approach, attempted to negotiate an end to the conflict with Crassus but was met with refusal.

As a result, Spartacus and his army broke through the Roman fortifications and retreated towards the Bruttium peninsula, followed closely by Crassus’s legions. In a skirmish with a portion of Spartacus’s army led by Gannicus and Castus, Crassus’s forces inflicted a significant defeat, killing 12,300 rebels.

Despite heavy losses, Crassus’ legions were struggling to contain Spartacus’s rebel army. The Roman cavalry, led by Lucius Quinctius, was ambushed and annihilated by escaping slaves. As the rebels’ morale faltered, they began to splinter, launching desperate attacks against Crassus’ forces.

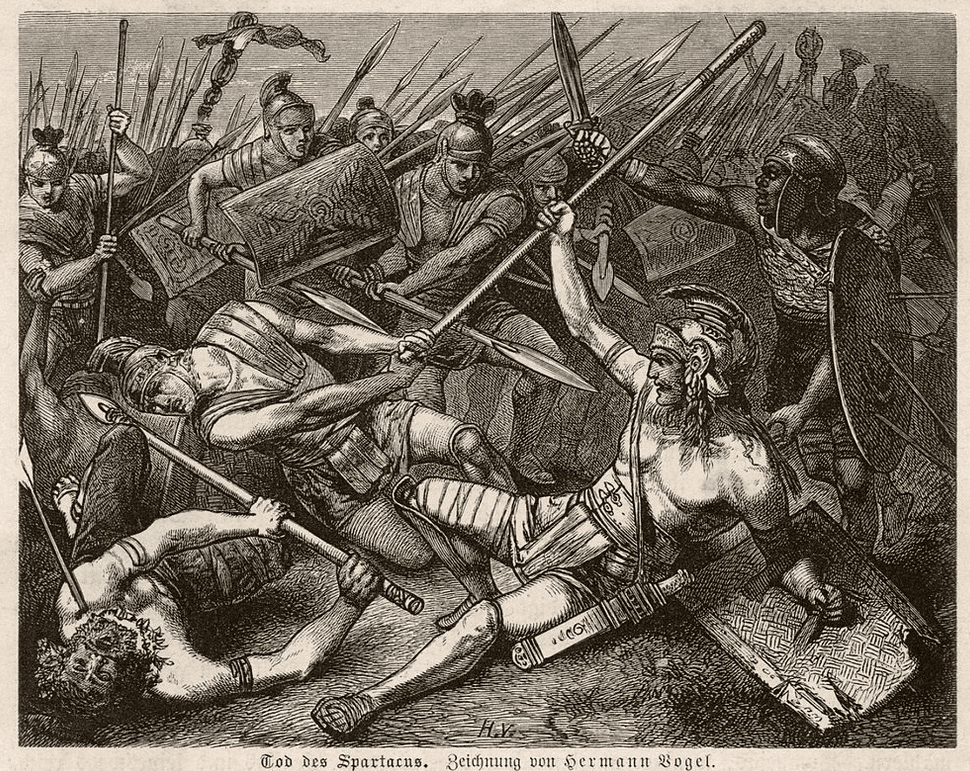

In a final, desperate stand at the Battle of the Silarius River, Spartacus, the legendary gladiator turned rebel leader, made a dramatic gesture that symbolized his unwavering determination. He slaughtered his horse before his troops, declaring that victory would bring more horses, but death would render them unnecessary. This act, perhaps imbued with a ritualistic significance, set the tone for the ensuing bloodbath.

Spartacus advanced with ferocious intent, cutting a swathe through the enemy ranks. His ultimate goal was believed to be Crassus, the Roman general leading the opposing forces. However, despite his valiant efforts, Spartacus fell in a hail of arrows, his body left unrecognizable amidst the carnage. The Roman victory was decisive, and Crassus, to instill fear in potential rebels, ordered the crucifixion of 6,000 surviving prisoners along the Appian Way. Though ancient historians claimed Spartacus perished in the battle, his body was never recovered. The Third Servile War was effectively ended, with Crassus claiming the decisive victory.

The war, however, was not yet over. Numerous fugitives attempted to escape northward, only to be intercepted by Pompey’s army in Etruria. Pompey’s annihilation of these remnants of the rebellion secured his own claim to fame and overshadowed Crassus’s earlier victory. He boasted that while Crassus had defeated the slaves in battle, he had eradicated the war’s very roots.

Despite his defeat and death, Spartacus’s legacy endured. His name became synonymous with rebellion and resistance, a symbol of hope for the oppressed. While Crassus and Pompey, the victorious generals, eventually met tragic ends, Spartacus’s memory lived on as a mythical hero of freedom.

The Third Servile War proved to be the final major slave uprising in Roman history. Rome would not experience another rebellion of this scale for centuries to come.